THE RESURRECTION OF THE POPE, 1979

I first glimpsed Pope John Paul II on television. He was blessing handicapped children in Ireland. “Do the children pray to God?” Unexpectedly, I began to cry. I found this reaction unsophisticated, not to mention threatening.

I called my old friend Michael, an ex-Catholic ex-Marxist, and mumbled, “I’m so confused about God.”

Michael was watching the same newscast. “You and everybody else.” Popes in our lifetime had been old, dull, and Italian, but John Paul II was a Polish poet and scholar who spoke half a dozen languages and seemed able to make large groups of people feel they were being individually addressed.

It was near the end of the 1970s. It was near the end of the second millennium since the death of Jesus. It was also near the end of the age of Pisces, and no one knew yet what it might be the beginning of. Math and science had begun sounding more and more like metaphysics, and time as a constant had collapsed along with Newton’s laws. The only certainty remaining was the speed of light, and the only apotheosis had been the shattering flashes at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

This was the context for the resurrection of the Pope.

I went early to Mass in Yankee Stadium, but I got excluded from the press box through a fortunate mix-up, because a group of policemen from the Bronx Arson Squad rescued me. The good-looking plainclothesman who seemed to be in charge took me to the Special Lounge where they would be stationed. He told me the Pope was running an hour late and that there was a cop under the altar as well as a fireman and a stretcher. He told me he used to be an undercover narcotics agent, but he wouldn’t have busted people for marijuana, or for personal amounts of cocaine. “I just wouldn’t, that’s all.” Then he told me he was Catholic but didn’t go to church anymore. He showed me the rosaries bulging in his jacket pockets, sent by cousins, aunts, uncles, to be made more holy by proximity to the Pope.

The sea of faithful stretched below us. The Special Lounges, which were not lighted, ranged through the second and third tiers, like gun slits in a fort. The chair the Pope would occupy looked as tiny as a toy down on second base, but this was Yankee Stadium, and the Pope’s coat of arms blazed on the scoreboard.

“This is wonderful, isn’t it,” the cop said.

“Yes,” I said, and meant it.

“It’s like…it’s like the World Series of the Holy Spirit.”

The Pope was running late, so I asked if I could leave my bag – no drugs in it, I assured him, just my notebooks and a pint of chicken pesto from Balducci’s – and I went back outside the stadium. Crowds still poured swiftly through the gates. I stood on the sidewalk, enjoying the polite, urgent movement, the shining faces, and a sense of goodness that was almost tangible. To those lucky enough to get tickets, Yankee Stadium was church, and this would be the biggest Sunday of their lives.

Out of curiosity I spent some minutes looking for scalpers. I found none, but I did meet two teenage boys who only had one ticket between them. Rather than choosing, they gave their ticket to a middle-aged man who had been weeping and saying, “I’ve got to go in there, I’ve got to go in there.”

At two of the entrances, the band of light at the top of the stadium appeared as a brilliant diadem, and entrants often found it startling. “I think that’s in really poor taste,” one nervous man said to his wife. “Wow,” I heard two different nuns say.

Then a little boy maybe 6 or 7 years old shouted, “Look, Mama!” And he pointed at the stadium lights and raised both arms above his head, as if he were witnessing a miracle.

Everybody knows how the light of reason lifted us out of ignorance and darkness. Everybody knows the rise of science has debunked superstition.But is religion merely superstition?

I am the truth, the light, and the way.

If, in the Western world, Christianity was once the light we held against suffering and death, if once the Bible had been humankind’s only encyclopedia, reason and science had cast revealed religion into the darkness it had once assuaged. To put this differently, after Darwin, punching holes in the biblical version of history was like shooting fish in a barrel. Biology now made the Virgin Birth seem silly. Two things I remember from my childhood in the 50s: the phrase “God is dead,” and the ditty “I don’t care if it rains or freezes, long as I got my plastic Jesus.”

My parents did drag me to various Protestant churches, but in adolescence I rebelled against baptism by going to a Catholic church and guiltily contemplating conversion. If Methodist doctrine seemed dull, I found the Latin Mass and the ancient music and all the religious statuary comforting. Catholicism embraced mystery. I could feel the weight of history pressing through it, and I could feel validation for my growing conviction that the inner world, those areas of the mind not accessible to reason, were more important than what my eyes could see. The Catholic church set off in me the same resonances, echoes, and prismatic glimpses that my budding sexuality did.

When I got married at the age of 18, I thought sex was holy. When I got divorced 7 years later, I still thought sex might be holy, but that marriage was part of the property system. Later I lived with various women, and if I no longer believed sex was sacred, I did think it was the most important thing that could happen between me and another person. As I got older, I began to think that religious ecstasy was nothing to sneeze at and that orgasm, well, it might not be more important than a sneeze.

Sex is a biological drive, a hunger, a pleasure, and a need, but I doubt it is a path. That sex could involve transcendence seems like something I once dreamed, a naïve lovely idea, like the Resurrection. Jesus died at 33, a pervasively bad age for male protagonists in novels.

A Jungian psychologist once told me that religion was like a hole in the psyche, and that, if God is dead, the need for God is not. Our quests for supranatural experiences have manifested in so many ways, among them psychedelic drugs, astrology, and the I Ching; an otherwise intelligent man once tried to explain how pyramids could sharpen razors.

We were needing a miracle. I went to one of the bars near the stadium, where the bartender was wearing a John Paul tee shirt. “Nah, I’m not Catholic, I just like the Pope, that’s all.” A drunk man touched my arm. “We are so lucky to be this close.” I could see in his eyes the ways he had been hurt. “This is history tonight. This is the most important man since Jesus.”

When I got back to the Special Lounge, the plans for distributing the Host were being announced over the P. A. system. Priests with leftover wafers should bring them to the Yankee dressing room, which was serving as the sacristy.

I began to get nervous and hungry, but it seemed inappropriate to mention that I’d planned to chow down on dinner from Balducci’s while everyone else was taking communion. In fact, this was a terrible idea, I asked my good-looking policeman who made the communion wafers. He said he was pretty sure nuns did. Even the brides of Christ have to bake the bread.

I kept staring at the altar at second base. Spectator sports, which are ritualized public releases, have become partial replacements for religion. Instead of church on Sunday morning, it’s now the games on Sunday afternoon. Football is closer to the extreme physicality of holy rollers, but baseball is more like the slow, mysterious repetitions of Catholicism. Baseball cards aren’t so different from saints’ cards, and for this particularly American mass, the setting mattered.

“LADIES AND GENTLEMEN! PLEASE TAKE YOUR SEATS! CLEAR THE WARNING TRACK!”

A procession of bishops and cardinals began. They wore white robes and white helmets, and from the back looked a lot like Ku Klux Klansmen. When they reached their seats they took off their weird hats, which I later found out are called mitres, and replaced them with skull caps.

“PLEASE CLEAR THE WARNING TRACK.”

The crowd sighed like a single organism and rose to its feet, as if sensing the Pope entering the stadium. Triumphal music boomed, and the gates behind center field opened. Phalanxes of uniformed policemen walked through, followed by a large group of Secret Service men wearing dark suits, earphones, and worried expressions.

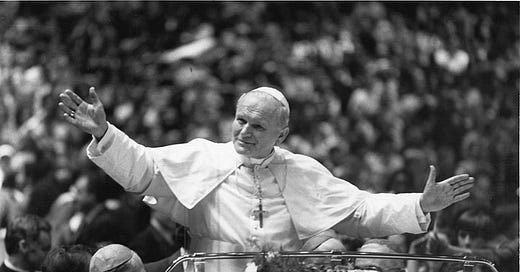

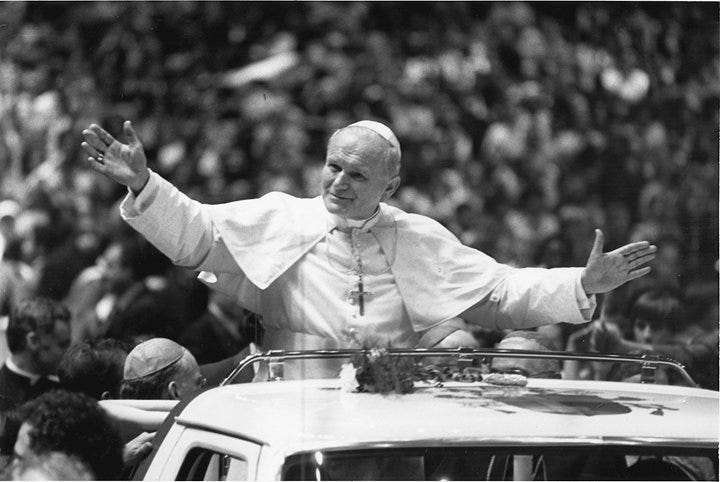

John Paul II entered the stadium standing in the open back of a Ford Bronco that slowly began circling the infield while he waved at the crowd like a Homecoming queen. As he kept waving and blessing the crowd, people with infield tickets ran beside the open car.

Everyone cheered with weird, tight enthusiasm, and flashbulbs flashed like fireflies. The entry music was “Lord Jesus Come,” and the 80,000 Catholics in the stadium sang “Jesus is risen! Jesus is coming!” while the choir responded with “Halleluia!” It was an amazing welcome.

Mass began. This was a traditional Mass, except that Helen Hayes gave the reading from Genesis in a throbbing voice. Whatever one might think about Catholicism, the Catholic Mass is splendid. I was gripped by pageantry, loveliness, history, and repetition.

The Catholic Mass is a repetition induction, a technique similar to meditation that I was taught in a hypnosis class. The Mass induces a sense of timelessness, hence of eternity. Einstein may have proved that time is actually alterable, but its subjective qualities were already familiar. Within the mind time jerks, hurries, swings slowly, dilates and contracts, and in sleep it disappears.

By the time of the Pope’s homily, I was loopy from the droning, the rising and falling of the readings, and the choir singing. I tried not to slip under, so I left the dark Special Lounge and entered the bright empty corridor.

Maybe the Lord does hear the cries of the poor, gives solace, maybe deprivation is purity and the meek will inherit another kingdom…..I went into the bathroom and washed my face.

The Pope’s homily was about the beggar Lazarus and the rich man who ignored him, but I was reminded of a story about a different Lazarus. “He is not dead but sleeping,” Jesus said, and Lazarus lived again. The Pope’s visit was awakening a sleeping dinosaur in the psychic landscape, and the homunculus of this dinosaur was clumping around in the more modern parts of my mind.

By the time Communion started, I thought my detachment was complete, but it was not. It had been foolish of me to think I could watch such an explicitly holy scene without a lot of mental twitching.

The priests fanned out through the crowd; there was a priest in each section on each level of the stadium. The communicants lined up. Some extended cupped palms to the priests, some took the wafer directly onto their tongues.

I asked my cop what the difference in styles represented. “With your hands, you get to feel closer to the Host, you know? It used to be you couldn’t touch it. Only the priest could touch it.”

Communion seemed to go on and on, and I asked my friend if he was going to do it. “No,” he said. “I haven’t been to confession in years, and you’ve got to be in a state of grace to take communion.”

“Are you sorry?”

He didn’t answer, and I wished I could take back my question. We were looking over the railing into the radiant faces of those receiving the body of Christ.

“When I was a kid,” he said, “I was afraid for the wafer to touch my teeth. I was afraid it was a sin. Can you imagine?”

“I can imagine,” I said. “When I was a kid I thought the rhythm method was something about how you did it. You know, I got rhy-thm, I got rhy- thm.”

I had managed to make him laugh, but then our laughter got sad.

“Listen,” I said, “would it be a terrible sin if I take Communion?”

His face worked with emotion. “Not for you. You’re not Catholic. For me it would be a sin.”

“Tell me how.”

He took my hands and cupped them together. “The priest will say, ‘This the body of Christ,’ and you will say ‘amen.’”

I went into the hall and stood in the line behind the priest In the next section. A Secret Service man was standing in line beside me. I watched one face after another opening itself to the wafer, and I began to shake. The Catholic Church, like the color white, is a construct to describe the absence of something. I felt an anguish I never expected.

I went back to the Special Lounge, grabbed my bag, and said a quick goodbye to my cop friend, who no longer seemed to notice me. Inside the nearby subway station a teenage girl was using fingernail polish to paint onto the faces on the billboards tears of blood.

My eyes ached, as if I’d been standing in a glare. The political implications of the Pope’s tour were troubling. The energy in Yankee Stadium had made the energy that drove the rock concerts and demonstrations of the 1960s seem puny. And, in the vivid silence that filled the stadium while the Pope was speaking, the rumble of a subway passing made me think of the sound preceding an avalanche.

++++++

If you want to respond to this story, I promise to answer……

It's so interesting for me as a writer to go back to these pieces and see what might make them better. This revision is less defended than the original, and therefore I think it has become deeper and more moving. You may or may not know that I've been sober in AA for 43 years, and finding a personal Higher Power is a fundamental part of that program. Like many members, I now simply call that power God, but, in my early sobriety, I found it especially difficult, as a lesbian, to come to terms with Xianity. However, as a friend who was dying of Aids liked to say, (he had to sit on cushions in meetings as his body wasted away), "God doesn't make junk, and God made me." I'm now comfortable in most churches and temples, and I forgive anyone who might judge me. These environments are often filled with spiritual energy, what the guru Muktananda called 'shakti,' and I can feel the presence of my Higher Power there.

I agree that this is one of your best, Blanche. It's so funny and so moving, truly wonderful.