RUBY, 1999

an excerpt from Children of Nod

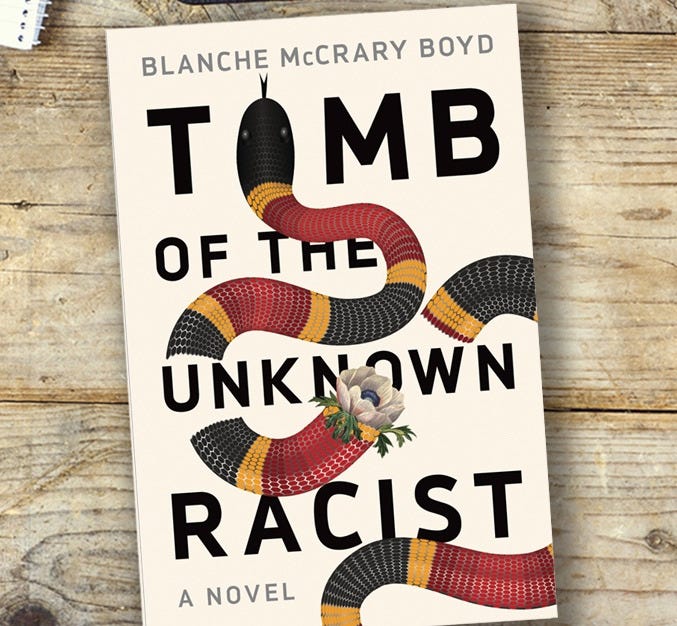

This is an excerpt from CHILDREN OF NOD, an early draft of my novel TOMB OF THE UNKNOWN RACIST, which became a Finalist for the PEN-Faulkner Award for Fiction in 2018. The book was released before the January 6 assault on the Capitol, so many readers simply did not believe the story I was telling. Now I think they - you - might, since TOMB remains relevant to our current political situation. The book is still around, and it’s also on Audible. I did not read it on Audible myself and can’t make myself listen.

TOMB OF THE UNKNOWN RACIST is a horrific story, and I’m sorry for that. I wrote it to try to answer an important moral and ethical question: What kinds of choices will white people have to make if we find these white extremists, even white terrorists among our family and friends?

The narrator here is Ellen Burns.

RUBY, 1999

(from the Children of Nod draft….)

I no longer believed that individual stories mattered, but I still valued kindness, and my niece Ruby seemed kind. Perhaps I cared too much about her, because my life soon crashed into the realities of Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, where she was incarcerated.

What Ruby had done to arrive at Bedford seemed too dreadful to contemplate, but hideous actions by women had become surprisingly familiar, yet they remained, for me, suffused with raw wonder, the shiny stuff of mystery.

At the age of 60 I find I am no longer ruled by an attraction to intensities, and I might have been content to spend my remaining years continuing to care for my mother, who has dementia but has become peaceful and sweet.

Ruby is my brother’s child.

Royce and his Vietnamese wife and their daughter had been gone from our lives until 1999, when, one night, Ruby interrupted my mother and me during our regular viewing of Jeopardy. Ruby, in tears and with childish dignity, appealed to the supposed kidnappers who she said had taken her children to please please please let her children go. Despite her Asiatic features, I recognized Ruby immediately. “That’s Royce’s daughter,” I whispered to my mother.

“Don’t you start crying.” She patted my hand. In my mother’s new world, there is no anguish. Sometimes she remembers that she had a fugitive son whom the FBI declared dead many years ago, but that memory no longer carries pain.

“I’m fine,” I said, although I wasn’t. I hadn’t seen Ruby since she was an infant, but, despite the difference in our ages, this young woman had the curve of my shoulders, some of my gestures, and her mouth resembled my own. Our common blood was immediately visible, and I felt too stunned to cry.

During the years we’d searched for Royce, we’d also looked for Ruby and her mother, but all three were gone. Every trace found by the FBI - and the two private detectives I’d hired - had vanished. We assumed that Ruby and her mother were in hiding from Royce, and that he had disappeared into a labyrinth of rightwing cells in the northwest, white men who planned to play a crucial role in a coming race war they believed was inevitable.

In the 1980s - and even much earlier - these organizations had been forming, and my brother, after denouncing Santane and Ruby, was thought to have joined the Silent Brotherhood, also called The Order. In 1984 the FBI destroyed the Silent Brotherhood in a blazing confrontation - they set on fire the house in which the group had taken refuge. Some members were apprehended as they tried to escape, but the leader chose to burn with the house. Royce was not found. I still don’t understand how this transformation could have happened to my brother, who had been a gentle survivalist living with a Vietnamese woman he’d met in an ashram. He delivered their daughter himself in their cabin in the woods, and he named her Ruby after the old black woman who had cared for him when we were children.

Then, several years after Royce disappeared, the FBI notified us that in a more detailed laboratory examination of the detritus of the fire, parts of my brother’s body had been located. They declared Royce Burns deceased and sent us some charred remains that we buried in a child-size coffin. “He was so wonderful when he was little,” my demented mother said, without irony.

The fate of Ruby’s children is now common knowledge. She had drugged them and placed them inside an old refrigerator in a cave that the Silent Brotherhood had called The Catacombs, first folding Lucia and River into the merciful poses of sleep. Afterwards, she drove back to the small house on the reservation where she lived with her current husband and hit herself a serious blow to the head with a hammer. Then she managed to tie herself up with silver duct tape before passing out. It was a scenario that fooled the police, her husband, and much of the public. After all, if she’d cracked her own skull, who could have tied her up? And the story she told to police and television cameras was so outlandish it must be true.

White supremacists, she claimed, had come to her home looking for her lost father. Maybe they had already known about her mixed blood; in any case, they discovered it when they saw her and her children. They’d laughed at her, a gook, a slant, a sand person, but had been outraged by her children, River, 4, and Lucia, 2, whose lineage had been further polluted by their Native and African-American fathers. These children were mongrels, the kidnappers said, abominations, offenses to God. Ruby had begged them not to take River and Lucia. She cried with the same dignity every time she recited this story.

The leader she described as a tall, narrowly built white man who said, “Nobody is innocent in the Land of Nod.” No, she did not know what the Land of Nod was, but she thought this whole mess must involve some kind of blackmail against her father. There must be some kind of fight about leadership, and they wanted to use his interracial past against him. She pleaded into the cameras for her father to come out of hiding and help save her babies.

The next morning, while my mother was eating her Cheerios with sliced bananas, I said, “Momma, I think Royce might still be alive.”

“That’s nice, honey.” She had taken the underpants off her head, so her silvery hair remained exactly coiffed, but she had put blue eye shadow on her lips. I let her do whatever she wants, unless we are going out.

I’m still not sure what Ruby intended with these intricate lies. She could not have believed anyone would be fooled by her story for long, and certainly not for the six days it took the police to locate the children’s bodies. And she probably did not really believe she would bring Royce out of hiding, even if he was still alive. Anyway, why would she want that, after his vicious rejection of her and her mother, and all the other terrible things he was said to have done? Sometimes I think Ruby has another motive. In any case, for the last four months, she has brought me out of the soothing light of my mother’s dementia and into the glare of public events I can’t manage to escape.

So now I am no longer staying in my mother’s Charleston condo, with its peaceful views of the Cooper River, and I no longer have the privilege of removing, at night, her crazed make-up, using tiny sponges and cue-tips, grateful that, eyes closed in what seems to be bliss, she allows me this tenderness. Except for a few weekend visits, I leave her care to hourly sitters and to Estelle, who stays some nights in the room where I slept.

Estelle is African-American, and almost 10 years younger than me. We met in an AA meeting in Cambridge, after recognizing our similar accents. Estelle says she is glad to have a side job, partly because I pay her in cash (the salary she draws at the hospital is ridiculous), and partly because I think she finds my mother harmless and entertaining.

Estelle and I were both fortunate enough to be educated in the Northeast – she is a nurse practitioner - and we had each believed we were coming home to a quieter, more gracious life in Charleston. Now we aren’t sure if things are significantly better than when we were children. Neither of us could comprehend what happened with Ruby and her children, but we did seem to understand each other. We remained comfortable, talking quietly, sometimes for hours, sitting in the dark beside my sleeping mother.

Now I am staying in Bedford Hills, in the garage apartment at Sister Irene’s house, and I go to the prison to see Ruby almost daily. When I am not in Bedford or in Charleston, I am ranging through Idaho and the Dakotas and Montana and New Mexico, trying to locate traces of my brother.

Sister Irene is a tough-talking nun in the privacy of her own home. She wears big muumuu’s and filthy, worn-out terrycloth slippers, and she keeps, for a hobby, some of the feral cats that hang around the prison; otherwise, the guards will shoot them. Her cats frighten me. Sometimes they invade the tiny studio over the garage, punching out the screens and waiting for me in the dark. I am not so much fun lately, if I can remember to close the windows.

At the prison Sister Irene dresses respectfully in the blue suits she wears as a habit, and on her feet are sensible navy pumps. Her short gray hair is kept neat. Only her eyes betray irony, wit, a subversive understanding. Only her eyes convey the possibility that at night she might spike her hair straight up with gel, drink beer, and sing a bawdy song. Most of the inmates love her. “I didn’t put you here," she tells them, "And I sure can’t get you out. So let’s make the best of it.” When she knows them better, she says, “I can’t absolve you, but God will.”

Ruby won’t talk to her at all.

Brilliant!!! More please.

Thanks….